I haven't heard the term "release backlog" in many months, but it's come up in three conversations over the past week. So, I want to share my thoughts on whether a team using an Agile project management approach should have a backlog known as a release in addition to the conventional Product and Sprint (or Iteration) Backlogs.

First, let's clarify what people mean when they refer to a "release backlog." A release backlog is a subset of the product backlog that is planned to be delivered in the coming release, typically a three- to six-month horizon. It would presumably contain the same type of items as on a product backlog. My preference for this, of course, would be user stories. So, at the start of some release planning horizon, a product owner with help from the team and other stakeholders would examine the product backlog, select some amount of high priority work and move those items to the release backlog. Later, in sprint (iteration) planning, the team would examine the release product and select some amount of work to do. (Notice how this already goes against existing agile literature that says the team selects top priority items for the sprint from the product backlog?)

I am opposed to the use of a release backlog for a couple of reasons:

First, in all projects that are not being done as fixed-scope contracts (and, arguably, even then) we don't know exactly what user stories or features will be delivered in a release. To say that there is a release backlog may not imply a guarantee that all features on it are delivered. However, it does create additional work as items are moved off back and forth between the product and release backlogs. This will happen as the team's velocity changes (even by small amounts) from sprint to sprint. If the release backlog is to show what a team will deliver in a release, it should contain an amount of work equal to the number of story points (or ideal days) times the number of remaining sprints. If you have an average velocity of 20 and 6 sprints left, then this type of backlog should contain 120 points worth of work. Suppose the team finishes 24 points of work in a sprint. The backlog is now down to 96 points (120-24) but should contain 100 (5 sprints left x an average velocity of 20). Things get even more difficult if that good velocity of 24 increases the team's average velocity to 21. In that case the backlog should contain 5x21=105 points of work; we need to move 9 points of work from the product backlog to the sprint backlog. If there's a release backlog, this moving of items back and forth from product to release backlog will happen every sprint.

Second, introducing a release backlog creates additional confusion. We've already overloaded the word "backlog" with "product backlog" and "sprint backlog." Why confuse things further with a third type of backlog unless there is an immensely compelling reason to do so?

Third, introducing the concept of a Release Backlog actually makes it harder for product owners to do one of the most important things they should be doing--looking at the features or user stories that just miss the cut of being in a release. When I look at a product backlog and count down the number of story points that I anticipate will be in the release, the most interesting thing to me is not necessarily the set of user stories that will make it into the release. I'm often just as interested in the next few user stories below that cut-off point. That is, I want to know what user stories won't quite make it into the release. After all, we say that one of the benefits of agile (on some, not all, projects) is the ability to decide later if we should release a few sprints early (if a lot has been done), on the planned date, or perhaps a sprint or two late if we want to add more functionality before a release. This is made more difficult with a Release Backlog because a product owner now needs to examine both Product and Release Backlogs to make these decisions.

So, what do I propose instead?

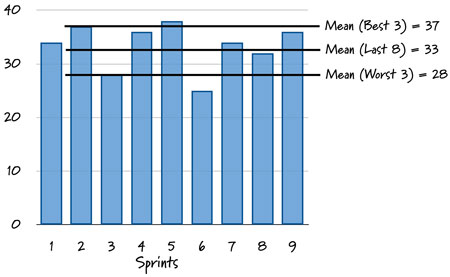

I advocate that all teams track their velocities. This leads to a graph like this:

This graph shows a team calculating three average velocities:

- Long term average, defined as the mean of the last eight sprints

- Worst case average, defined as the mean of the worst three chosen among the last eight sprints

- Best case average, defined as the mean of the best three chosen among the last eight sprints

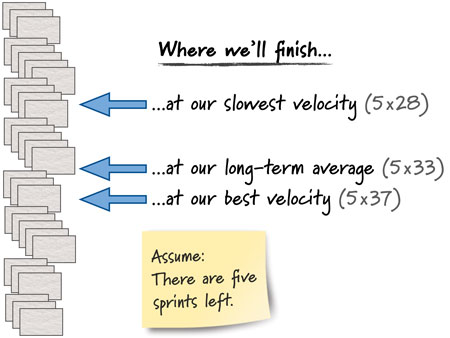

You can choose your own ways of calculating long-term, best-case, and worst-case average velocities. These are just the ones I like. We use these average velocities as shown in this figure:

In this figure, the product backlog is shown on the left as a stack of index cards. We use the three average velocities multiplied by the number of remaining sprints to draw arrows pointing into the product backlog. The range created by these arrows indicates the likely amount of work finished by the planned date. Our release plan is the work defined by the arrows. Rather than a Release Backlog as a new work product or artifact, my equivalent is the product backlog and these arrows pointing into it.

As you can imagine, predicting velocity as a range is much more likely to be accurate than using a single point estimate ("Our velocity is 31.") as has been implied by everyone I've heard talk about a Release Backlog. Additionally, looking at figures like these should make it apparent that the amount of work expected to be delivered in a release will change from sprint to sprint. Pointing arrows into a product backlog is much easier and more helpful than creating a new work product, the Release Backlog.

The discussion here is closed but join us in the Agile Mentors Community to further discuss this topic.

Go to AgileMentors.com