I’ve noticed something disturbing over the past two years. And it’s occurred uniformly with teams I’ve worked with all across the world. It’s the tendency to create an iterative waterfall process and then to call it agile.

An iterative waterfall looks something like this: In one sprint, someone (perhaps a business analyst working with a product owner) figures out what is to be built.

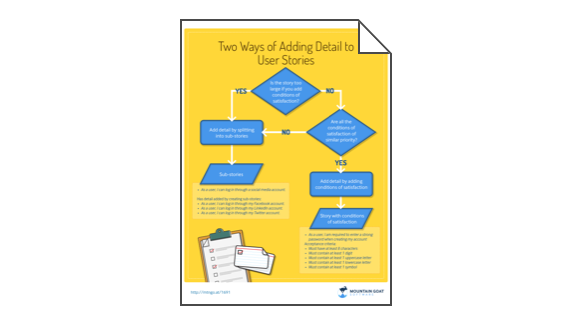

Because they’re trying to be agile, they do this with user stories. But rather than treating the user stories as short placeholders for future conversations, each user story becomes a mini-specification document, perhaps three to five pages long. And I’ve seen them longer than that.

These mini-specs/user stories document nearly everything conceivable about a given user story.

Because this takes a full sprint to figure out and document, a second sprint is devoted to designing the user interface for the user story. Sometimes, the team tries to be a little more agile (in their minds) by starting the design work just a little before the mini-spec for a user story is fully written.

Many on the team will consider this dangerous because the spec isn’t fully figured out yet. But, what the heck, they’ll reason, this is where the agility comes in.

Programmers are then handed a pair of documents. One shows exactly what the user story should look like when implemented, and the other provides all details about the story’s behavior.

No programming can start until these two artifacts are ready. In some companies, it’s the programmers who force this way of working. They take an attitude of saying they will build whatever is asked for, but you better tell them exactly what is needed at the start of the sprint.

Some organizations then stretch things out even further by having the testers work an iteration behind the programmers. This seems to happen because a team’s user stories get larger when each user story needs to include a mini-spec and a full UI design before it can be coded.

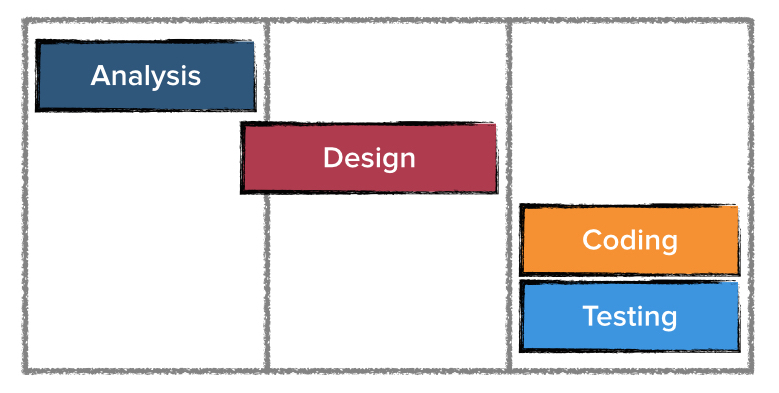

Fortunately, most teams realize that programmers and testers need to work together in the same iteration, but not extend that to being a whole team working together. This leads to the process shown in this figure.

This figure shows a first iteration devoted to analysis. A second iteration (possibly slightly overlapping with the first) is devoted to user experience design. And then a third iteration is devoted to coding and testing.

This figure shows a first iteration devoted to analysis. A second iteration (possibly slightly overlapping with the first) is devoted to user experience design. And then a third iteration is devoted to coding and testing.

This is not agile. It might be your organization’s first step toward becoming agile. But it’s not agile.

What we see in this figure is an iterative waterfall.

In traditional, full waterfall development, a team does all of the analysis for the entire project first. Then they do all the design for the entire project. Then they do all the coding for the entire project. Then they do all the testing for the entire project.

In the iterative waterfall of the figure above, the team is doing the same thing but they are treating each story as a miniature project. They do all the analysis for one story, then all the design for one story, then all the coding and testing for one story. This is an iterative waterfall process, not an agile process.

Ideally, in an agile process, all types of work would finish at exactly the same time. The team would finish analyzing the problem at exactly the same time they finished designing the solution to the problem, which would also be the same time they finished coding and testing that solution. All four of those disciplines (and any others I’m not using in this example) would all finish at exactly the same time.

It’s a little naïve to assume a team can always perfectly achieve that. (It can be achieved some times.) But it can remain the goal a team can work towards.

A team should always work to overlap work as much as possible. And upfront thinking (analysis, design and other types of work) should be done as late as possible and in as little detail as possible while still allowing the work to be completed within the iteration.

If you are treating your user stories as miniature specification documents, stop. Start instead thinking about each as a promise to have a conversation.

Feel free to add notes to some stories about things you want to make sure you bring up during that conversation. But adding these notes should be an optional step, not a mandatory step in a sequential process.

Leaving them optional avoids turning the process into an iterative waterfall process and keeps your process agile.

Last update: July 23rd, 2019