Agile Teamwork: How Great Teams Deliver

Learn about agile teams and agile teamwork—central components of any agile framework, including Scrum.

What Is Agile Teamwork?

Agile teamwork is when a small group of people work together to solve a compelling problem.

Hackman’s 2011 study “Collaborative Intelligence: Using Teams to Solve Hard Problems” asserts that “interdisciplinary and even inter-organizational teams are necessary to solve really hard problems.”

Why Teamwork Is Important for Agility

Teamwork matters for agility because teams are the heart and engine of an agile way of working.

Working as a team is essential to delivering a potentially shippable piece of value to customers at the end of an iteration. Teamwork is so important that the Agile Manifesto describes it in at least three different principles:

- Why Encourage Collaboration? “The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.”

- Why Prioritize Conversations? “The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.”

- Why Nurture Culture? “Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.”

How to Build Effective Teams

Teamwork is perhaps best described by the six conditions for team effectiveness, as defined by years of research from Richard Hackman and Ruth Wageman. They define three essentials and three enablers of teamwork.

Three Teamwork Essentials

- The ideal agile team structure includes the right people, with the diverse skills and perspectives necessary to accomplish the work.

- A true team is defined, works together to accomplish a goal, and is stable.

- A compelling purpose engages the team and points them in a shared direction.

Three Teamwork Enablers

- A sound culture enables each agile team to thrive. (Ensure each team is the right size, has defined norms, and has work that “makes sense to do as a team.”) Teams in an agile environment also need opportunities for team building.

- Team coaching helps each team optimize its resources, understand the various roles, cultivate an agile mindset, and recognize the mechanics and intent behind their chosen agile process and behind each agile practice.

- Structures and systems that promote agile principles and support great teamwork, including rewards for team performance.

How Is Agile Collaboration Different from Teamwork?

Agile collaboration is one essential ingredient in teamwork, but teamwork is about more than just being collaborative.

Teamwork is about being accountable and striving for improvement. It is being purposeful about maximizing the flow of work through the team.

Free Resources: How an Agile Team Works

Cross-Functional Teams

Cross-Functional Teams  High-Performing Teams

High-Performing Teams  Agility on Remote Teams

Agility on Remote Teams Creating Self-Organizing Teams

Creating Self-Organizing Teams  Teams Need Two Types of Authority

Teams Need Two Types of AuthorityWorking as an Agile Team

Good teams don't just happen. Without a clear problem to solve together, a cross-functional approach, and a sense of camaraderie, a team is only a group of people.

Agile software development teams learn how to make handoffs small, how to do a little bit of everything throughout the iteration, and how to bring in the optimal mix of product backlog items to make collaboration possible.

Make Handoffs Small

On teams using an agile methodology like Scrum, the unit of transfer between team members should be smaller than a product backlog item (typically, a user story). That is, although there will always be handoffs, you want them to be as small and frequent as possible.

An Example of Small Handoffs

Suppose an agile team is developing a new eCommerce application. The team chooses to work on this user story from its product backlog: As a shopper, I can select how I want items shipped based on the actual costs of shipping to my address so that I can make the best decision.

At the beginning of the iteration, members of the agile development team begin to discuss some of the general needs implicit in this feature:

- Which shipping companies (FedEx, UPS, etc.) do we support?

- Do we want to support overnight delivery? Two-day delivery? Three-day delivery?

- Are we going to charge a handling fee? On all items? A fixed amount or a sliding scale?

Once the agile team brings this backlog item into an iteration, the team members (developers) who anticipate working on it discuss where to begin with the product owner. Here that would include:

- The product owner

- An analyst who will get answers to the open issues

- One programmer

- One tester

Naturally, some backlog items will require more people or more than one programmer or tester.

Team Collaboration During a Sprint

Let's suppose this group of team members meet and agree to start by developing support for FedEx first. The programmer can begin designing, coding and unit testing support for FedEx.

While the programmer begins that, the product owner, analyst and tester discuss any high-level acceptance criteria that have not already been identified.

The tester can turn the acceptance criteria into automated tests. The analyst will work to get answers to the open issues. As the analyst does that, answers are communicated to the tester and programmer who will incorporate them into their work.

When the programmer and tester are both done, and the code passes the automated tests, the new functionality is added into the official build of the product. Ideally it is deployed as well.

The programmer and tester then work on adding support for UPS and add that to the build when done.

The Ideal Size for Handoffs

When teams are new to agile and Scrum, they tend to make handoffs too big. For example, the programmer might grab a product backlog item and finish all of the work on it before handing it over to a tester.

Work will flow more smoothly if the programmer instead hands work over each time an additional acceptance criteria or test is ready for validation by the tester. It’s possible this is too small to be practical in some cases (especially with globally distributed teams). However, it’s good to keep this size in mind as a goal.

Do a Little Bit of Everything

The agile team in the example I just discussed has learned to work by doing a little of everything all the time. They are embracing an agile approach to work.

At the beginning of an agile transformation, many new teams struggle with this concept. They might work in iterations, but inside the sprint, they continue to approach work in phases: an analysis phase followed by a programming phase followed by a testing phase.

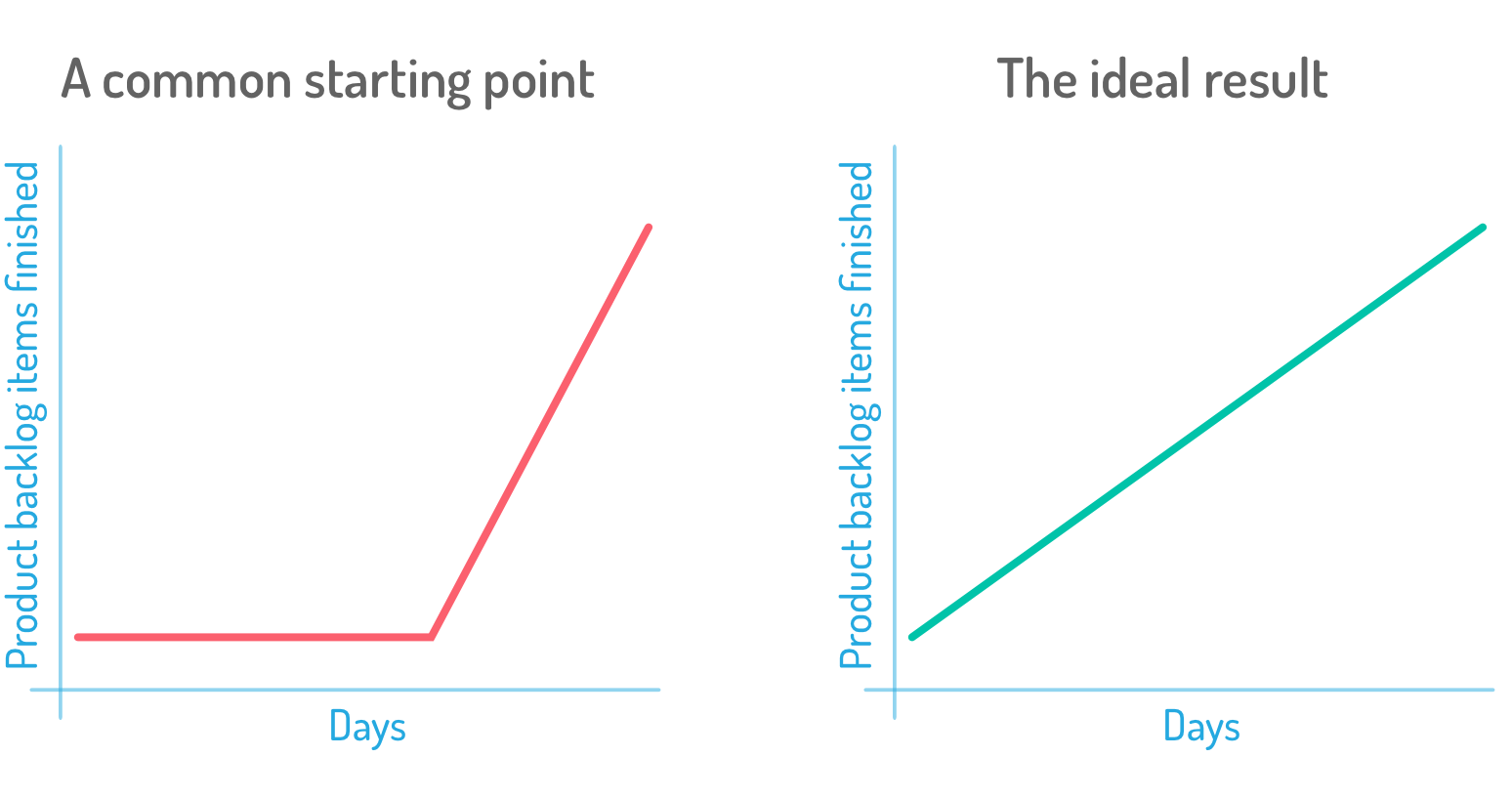

Signs Your Agile Team Might Be Stuck in a Phased Approach

- Does your team have a tendency to only finish product backlog items on last few days of the sprint?

- Are your testers complaining that they are given nothing to test until two days before the end of a sprint and then are expected to test everything quickly?

A good way to expose this problem is to create a chart of the number of product backlog items finished as of each day in the sprint. Here is an example:

For a collocated team, I like to hang this in the team area with no fanfare or explanation. Team members will notice the problem and, hopefully, start to find ways to finish product backlog items sooner.

For a distributed or remote team, I like to have this included on a product home page if team members regularly use a tool that can show this type of graph. If not, the Scrum Master can share their screen at the start of each daily scrum, along with any other information team members like to have visible during the meeting.

Include Backlog Items of Different Sizes

Doing a little bit of everything all the time and minimizing handoffs is easier with the right mix of product backlog items. During the sprint planning meeting, teams should pay attention to the sizes of the product backlog items they bring in.

For some product backlog items it will be difficult to create small handoffs. That’s fine. But you don’t want to plan a sprint with nothing but that type of item. If you did, it would likely shift too much testing to the end of the sprint.

Avoid that by bringing in some smaller product backlog items that can be handed off in multiple smaller pieces.

How to Encourage Teamwork

A team's agile coach /Scrum Master can encourage teamwork by helping teams understand how to break from their sequential work habits, foster open communication, and overlap work. Leaders in an agile organization can help by maximizing employees’ learning opportunities and giving teams the freedom to discover fresh ideas and approaches to problem solving.

Creating new teamwork habits can be challenging. Discover more about the many elements of teamwork.

Free Resources: Good Habits for Great Teams

Overlapping Work

Overlapping Work  Handoffs between Roles

Handoffs between Roles  Agile Collaboration

Agile Collaboration Rewarding Agile Teams

Rewarding Agile Teams  Scrum Teams and Speed

Scrum Teams and Speed  Download 25 Questions for Teams

Download 25 Questions for TeamsTeamwork and Agility

Good teamwork and being a good team member are critical skills to learn—every bit as critical as learning to be a Scrum Master or product owner. Yet effective teamwork skills are so often overlooked, even by certifying bodies such as Scrum Alliance and Scrum.org.

That’s why we offer private courses, video courses, group public course discounts, and onsite mentoring for teams. We cover the basics of the Scrum framework for agile project management, including the Scrum roles, Scrum meetings (e.g. sprint planning, sprint review), and Scrum artifacts, such as product backlogs and sprint backlogs.

But just as importantly, we work on skills to help your agile team members work together to deliver value each and every iteration.

That’s also why we developed our own Working as a Scrum Team course, offered for one team, multiple teams, or even just one team member (through a public offering). Learn more about how we can help.

Last update: November 19th, 2024