By 2026, most agile practitioners have plenty of scar tissue when it comes to estimating and planning.

I hear the same stories again and again. Estimates treated as promises. Plans turned into contracts. Teams punished for being wrong rather than rewarded for learning. Given experiences like those, it’s understandable that many teams conclude the solution is to eliminate estimating and planning altogether.

I think that’s a mistake.

Estimating and planning still matter—not because the future is predictable, but because it isn’t. They matter because teams and organizations still have to make decisions about what to work on, what to defer, and what risks they’re willing to accept.

In this post, I’ll explain why I believe that, and what estimating and planning look like when they’re used responsibly by modern agile teams.

You Can’t Avoid Estimating—Only Hide It

Any time you choose one piece of work over another, you’re estimating.

You’re estimating cost, value, risk, or effort—even if you never put a number on it. Over the years, I’ve worked with teams who proudly claimed they “don’t estimate,” only to watch them make decisions based on unspoken assumptions about size and difficulty.

The estimates were still there; they were just invisible and unexamined.

The real choice isn’t whether to estimate. It’s whether estimates are explicit or implicit, discussed or denied. In my experience, explicit estimates create transparency, while implicit estimates create the illusion that no one is guessing.

(For a deeper look at why teams struggle with this, see my earlier post on why we think we’re bad at estimating.)

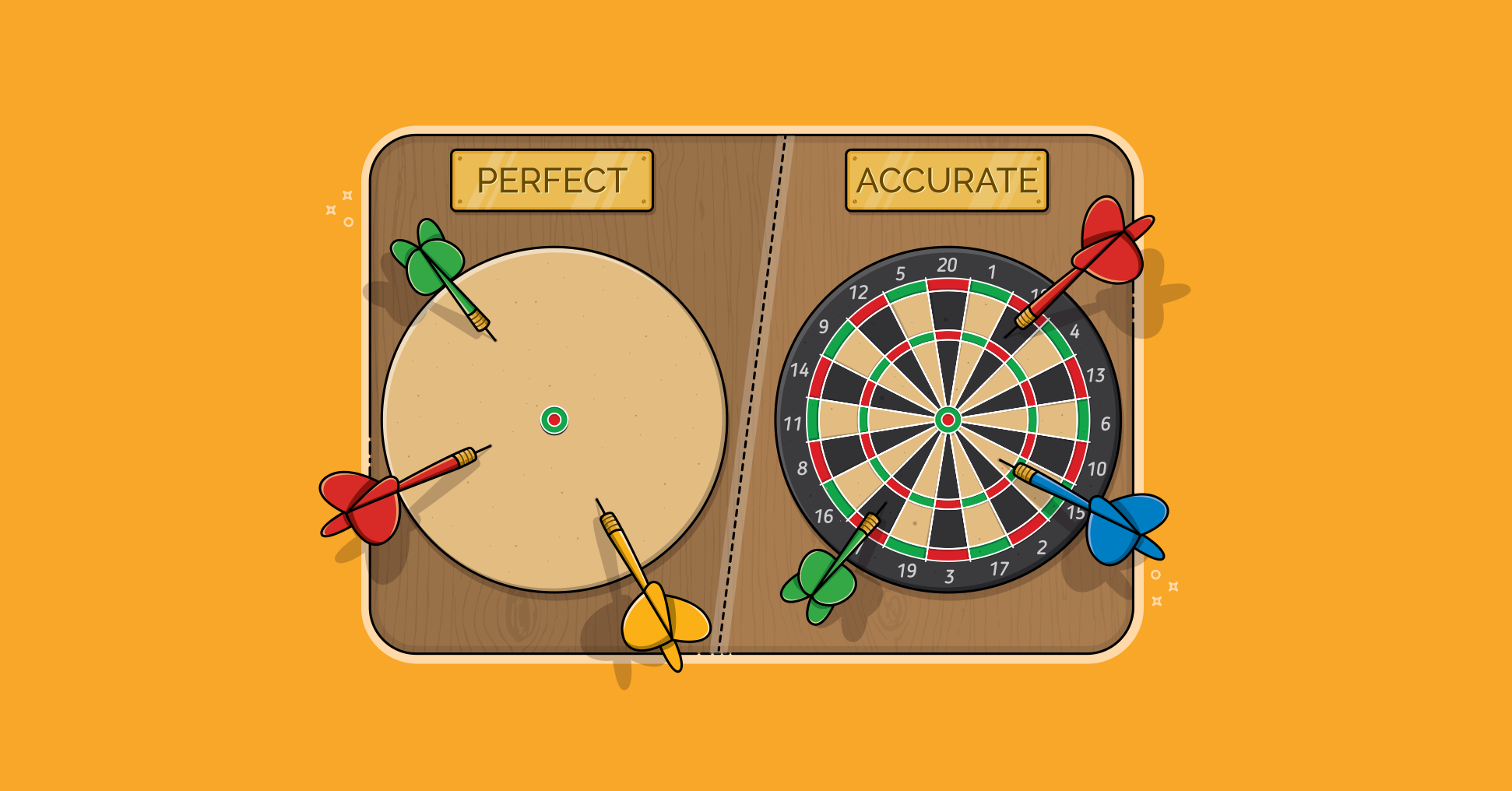

Estimates Are for Decisions, Not Predictions

One of the most damaging beliefs in agile is that estimates exist to be accurate.

That framing turns every estimate into a test—and every miss into a failure. It also explains why estimating generates so much anxiety.

In healthy agile environments, estimates exist to support decisions. They help answer questions like: Is this initiative worth starting? Should we do this now or later? What are we trading off if we choose this?

A much better question than “Is this estimate accurate?” is this:

Is this estimate good enough to support the decision we’re making?

I’ve written more about tying estimates to decisions in posts like How Can We Get the Best Estimates of Story Size?. When teams ask the right question, estimation becomes far less contentious—and far more useful.

Wrong Estimates Are Not Failures

I often hear people say, “Estimates are always wrong.” They’re usually saying this with some frustration—and they’re not entirely wrong.

But being wrong isn’t the real problem.

Estimates are hypotheses. Reality supplies the data.

I’m reminded of this every time I run a training class. If it’s a class I’ve taught before I can estimate almost perfectly how long it will take to set up exercises in our Team Home software, how long it will take to prepare the slides, and how long it will take to review my presenter notes.

When it’s a new class, though, all bets are off. When my estimate is off, it doesn’t mean estimating was pointless. It tells me exactly what I didn’t yet know.

That’s how estimation works on agile teams as well. When an estimate misses, teams can discover hidden complexity, surface faulty assumptions, and build shared understanding.

The failure isn’t being wrong. The failure is treating estimates as promises—and punishing teams when reality turns out to be more complex than anyone anticipated.

Planning Does Not Reduce Adaptability

Planning is often portrayed as the opposite of agility. In practice, the opposite is true.

Good planning aligns assumptions and intent. It gives teams a shared starting point so they can adjust quickly when things change.

What actually reduces adaptability is planning too far into the future, over-committing to uncertain work, and treating plans as contracts instead of guides.

I like to think of planning the way I think about planning a hike. You don’t plan because you expect the weather to behave. You plan so you know how to respond when it doesn’t.

Flow Metrics and Estimation Work Best Together

Flow metrics have added valuable empirical grounding to agile work. They help teams understand how work has flowed in the past.

But flow metrics struggle with novelty. Whenever work is new, risky, or meaningfully different from what a team has done before, historical averages become less reliable.

That’s where estimation still helps—not to predict precisely, but to reason about what might be different this time.

Rather than choosing sides, I encourage teams to use both. Flow metrics ground conversations in data. Estimation for thinking through new work.

Planning Is a Human‑Centered Practice

One of the surprises I’ve seen over the years is that removing planning often increases pressure on teams rather than relieving it.

Without clear boundaries, work expands. Priorities shift constantly. Over‑commitment becomes invisible. Teams feel like they’re always behind, even when they’re doing good work.

Lightweight planning creates focus and boundaries. It gives teams a chance at sustainable pace.

Planning isn’t bureaucracy. It’s one of the ways teams protect themselves from chaos.

When Estimation Becomes Harmful

Estimation has gone wrong when numbers are used to evaluate individuals, when variance is punished rather than examined, and when precision is demanded where uncertainty is high.

Those are not failures of estimation techniques. They are failures of leadership intent.

When leaders use estimates to learn, teams behave one way. When leaders use estimates to blame, teams behave very differently.

Healthier Estimating and Planning in 2026

The most effective teams I work with today estimate and plan differently than they did a decade ago.

They use ranges instead of single numbers. They estimate less frequently, but more intentionally. They revisit assumptions often and tie every estimate to a clear decision.

They’re also careful with language, because language shapes behavior. They talk about forecasts, not promises. Intent, not guarantees. Learning, not accuracy.

A Simple Test

Before estimating or planning, I encourage teams to pause and ask three questions:

- What decision does this support?

- What happens if we’re wrong?

- Who will use this information—and how?

If those questions don’t have clear answers, the problem usually isn’t how the team is estimating.

It’s why they’re estimating.

Closing Thought

Uncertainty isn’t a flaw in agile systems. It’s the reality those systems are designed to handle.

Estimation and planning don’t eliminate uncertainty. They help teams navigate it—together.

If this way of thinking resonates with you, you may also enjoy exploring the articles and courses available at Mountain Goat Software. They’re all grounded in the same belief: that agile works best when we replace false certainty with learning, judgment, and trust.

Last update: January 27th, 2026